GREEK ORIENTEERING CLUB OF THESSALONIKI

For more information about the sport internationally search the site: www.orienteering.org For more information

about the sport in Greece search the site: www.orienteering.org.gr

E-mail: compass7@ath.forthnet.gr Konstantinos

Koukouris, Ph.D

Koukouris, Ph.D

Reference: Kjetil Kjernsmo’s (1997-2000) illustrated

guide on how to use a compass. http://www.learn-orienteering.org/old/fog1.html

kjetikj@astro.uio.no

guide on how to use a compass. http://www.learn-orienteering.org/old/fog1.html

kjetikj@astro.uio.no

It’s when you use both compass

and map the compass is really good, and you will be able to navigate safely and

accurately in terrain you’ve never been before without following trails. But it’ll take some training and experience,

though. The most

important steps are summarized below.

and map the compass is really good, and you will be able to navigate safely and

accurately in terrain you’ve never been before without following trails. But it’ll take some training and experience,

though. The most

important steps are summarized below.

2. Rotate the compass housing

until the orienting arrow and lines point N on the map.

until the orienting arrow and lines point N on the map.

3. Rotate the map and compass

together until the red end of the compass needle points north.

together until the red end of the compass needle points north.

4. Follow the direction of travel

arrow on the compass, keeping the needle aligned with the orienting arrow on

the housing.

arrow on the compass, keeping the needle aligned with the orienting arrow on

the housing.

Take a map. In our first example, we look at a

map made for orienteering, and it is very detailed. You want to go from A,

to B. Of course, to use this method successfully, you’ll have

to know you really are at A. What you do, is that you put your compass on the map so that the edge of

the compass is at A. The edge you must be using, is the edge that is parallel

to the direction of travel arrow. And

then, put B somewhere along the same edge. Of course, you could use the direction arrow itself,

or one of the parallel lines, but usually, it’s more convenient to use the

edge. The edge of the compass, or rather the direction

arrow, must point

map made for orienteering, and it is very detailed. You want to go from A,

to B. Of course, to use this method successfully, you’ll have

to know you really are at A. What you do, is that you put your compass on the map so that the edge of

the compass is at A. The edge you must be using, is the edge that is parallel

to the direction of travel arrow. And

then, put B somewhere along the same edge. Of course, you could use the direction arrow itself,

or one of the parallel lines, but usually, it’s more convenient to use the

edge. The edge of the compass, or rather the direction

arrow, must point

from A to B! And again, if you do this wrong,

you’ll walk off in the exact opposite direction of what you want. So take a second look. Beginners often make

this mistake as well.

Keep the compass steady on the map. What you

are going to do next is that you are going to align the orienting lines and the

orienting arrow with the meridian lines of the map. The lines on the map going

north, that is while you have the edge of the compass carefully aligned from A

to B, turn the compass housing so that the orienting lines in the compass

housing are aligned with the meridian lines on the map. During this process,

you don’t mind what happens to the compass needle.

There are a number of serious mistakes that can be made here. Let’s take

the problem with going in the opposite direction first. Be absolutely certain that you

know where north is on the map, and be sure that the orienting arrow is

pointing towards the north on the map. Normally, north will be up on the map. The possible mistake is to let the orienteering

arrow point towards the south on the map. And then, keep an eye on the edge of

the compass. If

the edge isn’t going along the line from A to B when you have finished turning

the compass housing, you will have an error in your direction, and it can take

you off your course. When you are sure you have the compass housing right, you

may take the compass away from the map. And now, you can in fact read the

azimuth off the housing, from where the housing meets the direction arrow.

are going to do next is that you are going to align the orienting lines and the

orienting arrow with the meridian lines of the map. The lines on the map going

north, that is while you have the edge of the compass carefully aligned from A

to B, turn the compass housing so that the orienting lines in the compass

housing are aligned with the meridian lines on the map. During this process,

you don’t mind what happens to the compass needle.

There are a number of serious mistakes that can be made here. Let’s take

the problem with going in the opposite direction first. Be absolutely certain that you

know where north is on the map, and be sure that the orienting arrow is

pointing towards the north on the map. Normally, north will be up on the map. The possible mistake is to let the orienteering

arrow point towards the south on the map. And then, keep an eye on the edge of

the compass. If

the edge isn’t going along the line from A to B when you have finished turning

the compass housing, you will have an error in your direction, and it can take

you off your course. When you are sure you have the compass housing right, you

may take the compass away from the map. And now, you can in fact read the

azimuth off the housing, from where the housing meets the direction arrow.

Be sure that the housing

doesn’t turn, before you reach your target B!

Hold the compass in your hand. And

now you’ll have to hold it quite flat, so that the compass needle can turn. Then turn yourself, your hand,

the entire compass, just make sure the compass housing doesn’t turn, and turn

it until the compass needle is aligned with the lines inside the compass

housing.

doesn’t turn, before you reach your target B!

Hold the compass in your hand. And

now you’ll have to hold it quite flat, so that the compass needle can turn. Then turn yourself, your hand,

the entire compass, just make sure the compass housing doesn’t turn, and turn

it until the compass needle is aligned with the lines inside the compass

housing.

The

mistake is again to let the compass needle point towards the south. The red

part of the compass needle must point at north in the compass

housing, or you’ll go in the opposite direction.

mistake is again to let the compass needle point towards the south. The red

part of the compass needle must point at north in the compass

housing, or you’ll go in the opposite direction.

It’s time to walk off. But to do that with optimal accuracy, you’ll have

It’s time to walk off. But to do that with optimal accuracy, you’ll haveto do that in a special way as well. Hold the compass in your hand, with the

needle well aligned with the orienting arrow. Then aim, as carefully as you

can, in the direction of travel-arrow is pointing. Fix your eye on some special

feature in the terrain as far as you can see in the direction. Then go there.

Be sure as you go that the compass housing doesn’t turn. If you’re in a dense

forest, you might need to aim several times. Hopefully, you will reach your

target B when you do this. Unfortunately, sometimes, for some quite often, it

is even more complicated. There is something called magnetic declination.

And then, for hiking, you wouldn’t use orienteering maps.

Using

the compass alone

the compass alone

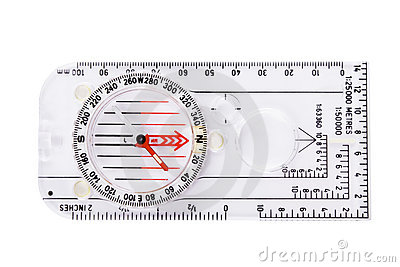

The first thing you need to

learn, are the directions. North, South, East and West.

North is the most important. There are several kinds of compasses, one kind to

attach to the map, one kind to attach to your thumb. The thumb-compass is used

mostly by orienteers who just want to run fast. I would recommend the third

kind of compass. Let’s take a look at it: You see this red and black arrow? We

call it the compass needle. Well, on some compasses it might be red and

white for instance, but the point is, the red part of it is always pointing

towards the earth’s magnetic north pole.

learn, are the directions. North, South, East and West.

North is the most important. There are several kinds of compasses, one kind to

attach to the map, one kind to attach to your thumb. The thumb-compass is used

mostly by orienteers who just want to run fast. I would recommend the third

kind of compass. Let’s take a look at it: You see this red and black arrow? We

call it the compass needle. Well, on some compasses it might be red and

white for instance, but the point is, the red part of it is always pointing

towards the earth’s magnetic north pole.

But if you don’t want to go

north, but a different direction? Hang on and I’ll tell you.

You’ve got this turnable thing on your compass. We call it the Compass

housing. On the edge of the compass housing, you will probably have a

scale. From 0 to 360 or from 0 to 400. Those are the degrees or the azimuth

(or you may also call it the bearing in some contexts). And you should have the

letters N, S, W and E for North, South, West and East. If you want to go in a

direction between two of these, you would combine them. If you would like to go

in a direction just between North and West, you simply say: “I would

like to go Northwest “.

north, but a different direction? Hang on and I’ll tell you.

You’ve got this turnable thing on your compass. We call it the Compass

housing. On the edge of the compass housing, you will probably have a

scale. From 0 to 360 or from 0 to 400. Those are the degrees or the azimuth

(or you may also call it the bearing in some contexts). And you should have the

letters N, S, W and E for North, South, West and East. If you want to go in a

direction between two of these, you would combine them. If you would like to go

in a direction just between North and West, you simply say: “I would

like to go Northwest “.

Let’s use that as an

example: You want to go northwest. What you do, is that you find out where on

the compass housing northwest is. Then you turn the compass housing so that

northwest on the housing comes exactly there where the large direction of

travel-arrow meets the housing.

Hold the compass in your hand. And you’ll have to hold it quite flat, so that

the compass needle can turn. Then turn yourself, your hand, the entire compass,

just make sure the compass housing doesn’t turn, and turn it until the compass

needle is aligned with the lines inside the compass housing.

Now, time to be careful!. It is extremely important that the red,

north part of the compass needle points at north in the compass housing. If

south points at north, you would walk off in the exact opposite direction of

what you want! And it’s a very common mistake among beginners. So always take a

second look to make sure you did it right!

A second problem might be local magnetic attractions. If you are carrying

something of iron or something like that, it might disturb the arrow. Even a

staple in your map might be a problem. Make sure there is nothing of the sort

around. There is a possibility for magnetic attractions in the soil as well,

“magnetic deviation“, but they are rarely seen. Might occur if

you’re in a mining district.

example: You want to go northwest. What you do, is that you find out where on

the compass housing northwest is. Then you turn the compass housing so that

northwest on the housing comes exactly there where the large direction of

travel-arrow meets the housing.

Hold the compass in your hand. And you’ll have to hold it quite flat, so that

the compass needle can turn. Then turn yourself, your hand, the entire compass,

just make sure the compass housing doesn’t turn, and turn it until the compass

needle is aligned with the lines inside the compass housing.

Now, time to be careful!. It is extremely important that the red,

north part of the compass needle points at north in the compass housing. If

south points at north, you would walk off in the exact opposite direction of

what you want! And it’s a very common mistake among beginners. So always take a

second look to make sure you did it right!

A second problem might be local magnetic attractions. If you are carrying

something of iron or something like that, it might disturb the arrow. Even a

staple in your map might be a problem. Make sure there is nothing of the sort

around. There is a possibility for magnetic attractions in the soil as well,

“magnetic deviation“, but they are rarely seen. Might occur if

you’re in a mining district.

When you are sure you’ve got

it right, walk off in the direction the direction of travel-arrow is pointing.

To avoid getting off the course, make sure to look at the compass quite

frequently, say every hundred meters at least.

But you shouldn’t stare down on the compass. Once you have the direction, aim

on some point in the distance, and go there. But this gets more important when

you use a map.

it right, walk off in the direction the direction of travel-arrow is pointing.

To avoid getting off the course, make sure to look at the compass quite

frequently, say every hundred meters at least.

But you shouldn’t stare down on the compass. Once you have the direction, aim

on some point in the distance, and go there. But this gets more important when

you use a map.

There is something you

should look for to avoid going in the opposite direction: The Sun. At noon, the

sun is roughly in South (or in the north on the southern hemisphere), so if you

are heading north and have the sun in your face, it should ring a bell.

should look for to avoid going in the opposite direction: The Sun. At noon, the

sun is roughly in South (or in the north on the southern hemisphere), so if you

are heading north and have the sun in your face, it should ring a bell.

When do you need this

technique? If you are out there without a map, and you don’t know where you

are, but you know that there is a road, trail, stream, river or something long

and big you can’t miss if you go in the right direction. And you know in what

direction you must go to get there, at least approximately what direction. Then

all you need to do, is to turn the compass housing, so that the direction you

want to go in, is where the direction of travel-arrow meets the housing. And

follow the above steps. But why isn’t this sufficient? It is not very accurate.

You are going in the right direction, and you won’t go around in circles, but

you’re very lucky if you hit a small spot this way. And that’s why I’m not

talking about declination here. And because that is something connected

with the use of maps. But if you have a mental image of the map and know what

it is, do think about it. But I think you won’t be able to be so accurate so

the declination won’t make a difference. If you are taking a long hike in

unfamiliar terrain, you should always carry a good map that covers the terrain.

Especially if you are leaving the trail. It is in this interaction between the

map and a compass, that the compass becomes really valuable. And that is dealt witKjetil

Kjernsmo’s illustrated guide on

technique? If you are out there without a map, and you don’t know where you

are, but you know that there is a road, trail, stream, river or something long

and big you can’t miss if you go in the right direction. And you know in what

direction you must go to get there, at least approximately what direction. Then

all you need to do, is to turn the compass housing, so that the direction you

want to go in, is where the direction of travel-arrow meets the housing. And

follow the above steps. But why isn’t this sufficient? It is not very accurate.

You are going in the right direction, and you won’t go around in circles, but

you’re very lucky if you hit a small spot this way. And that’s why I’m not

talking about declination here. And because that is something connected

with the use of maps. But if you have a mental image of the map and know what

it is, do think about it. But I think you won’t be able to be so accurate so

the declination won’t make a difference. If you are taking a long hike in

unfamiliar terrain, you should always carry a good map that covers the terrain.

Especially if you are leaving the trail. It is in this interaction between the

map and a compass, that the compass becomes really valuable. And that is dealt witKjetil

Kjernsmo’s illustrated guide on

Magnetic

Declination

Declination

The

compass is pointing towards the magnetic northpole, and the map is

pointing towards the geographic northpole, and that is not the same

place. To make things even more complicated, there is on most hiking-maps

something (that is very useful) called the UTM-grid. This grid doesn’t

have a real north pole, but in most cases, the lines are not too far away from

the other norths. Since this grid covers the map, it is convenient to use as

meridians.

compass is pointing towards the magnetic northpole, and the map is

pointing towards the geographic northpole, and that is not the same

place. To make things even more complicated, there is on most hiking-maps

something (that is very useful) called the UTM-grid. This grid doesn’t

have a real north pole, but in most cases, the lines are not too far away from

the other norths. Since this grid covers the map, it is convenient to use as

meridians.

On most orienteering maps

(newer than the early 70’s), this is corrected, so you won’t have to worry

about it. But on topographic maps, this is a problem. First, you’ll have to

know how large the declination is, in degrees. This depends on where on the

earth you are. So you will have to find out before you leave home. Or somewhere

on the map, it says something about it. One thing you have to remember in some

areas, the declination changes significantly, so you’ll need to know what it is

this year. If you are using a map with a “UTM-grid”, you want to know how this grid differs from the

magnetic pole.

(newer than the early 70’s), this is corrected, so you won’t have to worry

about it. But on topographic maps, this is a problem. First, you’ll have to

know how large the declination is, in degrees. This depends on where on the

earth you are. So you will have to find out before you leave home. Or somewhere

on the map, it says something about it. One thing you have to remember in some

areas, the declination changes significantly, so you’ll need to know what it is

this year. If you are using a map with a “UTM-grid”, you want to know how this grid differs from the

magnetic pole.

Στους χάρτες προσανατολισμού δεν χρειάζεται να ανησυχούμε για την μαγνητική

απόκλιση. Αλλά στους τοπογραφικούς χάρτες αυτό είναι ένα πρόβλημα. Για να

κάνουμε τα πράγματα ακόμη πιο πολύπλοκα στους περισσότερους πεζοπορικούς χάρτες

υπάρχει κάτι που ονομάζεται UTM–grid. Αυτό το δικτυωτό πλέγμα δεν έχει πραγματικό βόρειο πόλο

αλλά στις περισσότερες περιπτώσεις οι γραμμές δεν απέχουν πολύ μακριά από τον

μαγνητικό βορρά και τον πραγματικό βορρά. Σε μερικές περιοχές η απόκλιση

αλλάζει σημαντικά. Γι’ αυτό χρειάζεται να γνωρίζουμε πόση είναι αυτή τη χρονιά.

απόκλιση. Αλλά στους τοπογραφικούς χάρτες αυτό είναι ένα πρόβλημα. Για να

κάνουμε τα πράγματα ακόμη πιο πολύπλοκα στους περισσότερους πεζοπορικούς χάρτες

υπάρχει κάτι που ονομάζεται UTM–grid. Αυτό το δικτυωτό πλέγμα δεν έχει πραγματικό βόρειο πόλο

αλλά στις περισσότερες περιπτώσεις οι γραμμές δεν απέχουν πολύ μακριά από τον

μαγνητικό βορρά και τον πραγματικό βορρά. Σε μερικές περιοχές η απόκλιση

αλλάζει σημαντικά. Γι’ αυτό χρειάζεται να γνωρίζουμε πόση είναι αυτή τη χρονιά.

You don’t align the orienting lines

with the grid lines pointing west or east, or south for that matter. When you

have taken out a course like you’ve learned, you must add or subract an angle,

and that angle is the angle you found before you left home, the angle between

the grid lines or meridians and the magnetic north. The declination is given as

e.g. “15 degrees east”. When you look at the figure, you can pretend

that plus is to the right, or east, and minus is to the left and west. Like a

curved row of numbers. So when something is more than zero you’ll subtract

to get it back to zero. And if it is less, you’ll add. So in this case

you’ll subtract 15 degrees to the azimuth, by turning the compass housing,

according to the numbers on the housing. Now, finally, the direction of

travel-arrow points in the direction you want to go. Again, be careful to aim

at some distant object and off you go. You may not need to find the declination

before you leave home, actually. There is a fast and pretty good method to find

the declination whereever you are. This method has also the advantage that

corrects for local conditions that may be present This is what you do:

with the grid lines pointing west or east, or south for that matter. When you

have taken out a course like you’ve learned, you must add or subract an angle,

and that angle is the angle you found before you left home, the angle between

the grid lines or meridians and the magnetic north. The declination is given as

e.g. “15 degrees east”. When you look at the figure, you can pretend

that plus is to the right, or east, and minus is to the left and west. Like a

curved row of numbers. So when something is more than zero you’ll subtract

to get it back to zero. And if it is less, you’ll add. So in this case

you’ll subtract 15 degrees to the azimuth, by turning the compass housing,

according to the numbers on the housing. Now, finally, the direction of

travel-arrow points in the direction you want to go. Again, be careful to aim

at some distant object and off you go. You may not need to find the declination

before you leave home, actually. There is a fast and pretty good method to find

the declination whereever you are. This method has also the advantage that

corrects for local conditions that may be present This is what you do:

- Determine by map inspection the grid azimuth from

your location to a known, visible, distant point. The further away, the

more accurate it gets. This means you have to know where you are, and be

pretty sure about one other feature in the terrain. - Sight on that distant point with the compass and

note the magnetic azimuth. You do that by turning the compass housing so

that it is aligned with the needle. You may now read the number from the

housing where it meets the base of the direction of travel-arrow. - Compare the two azimuths. The difference is the

declination. - Update as necessary. You shouldn’t need to do

this very often, unless you travel in a terrain with lots of mineral

deposits.

If you live in an area where

you don’t go far for it to change between east and west, it is so small you

wouldn’t need to worry about it anyway. So it’s best to just remember whether

you should add or subtract.

you don’t go far for it to change between east and west, it is so small you

wouldn’t need to worry about it anyway. So it’s best to just remember whether

you should add or subtract.

Uncertainty

You

can’t always expect to hit exactly what you are looking for. In fact, you must

expect to get a little off course. How much you get off course depends very

often on the things around you. How dense the forest is, fog, visibility

is a keyword. And of course, it depends on how accurate you are. You do

make things better by being careful when you take out a course, and it is

important to aim as far ahead as you can see.

can’t always expect to hit exactly what you are looking for. In fact, you must

expect to get a little off course. How much you get off course depends very

often on the things around you. How dense the forest is, fog, visibility

is a keyword. And of course, it depends on how accurate you are. You do

make things better by being careful when you take out a course, and it is

important to aim as far ahead as you can see.

In normal forest conditions

we say that as a rule of thumb, the uncertainty is one tenth of the distance

traveled. So if it is like in the figure, you go 200 meters on course, it

is possible that you end up a little off course, 20 meters or so. If

you’re looking for something smaller than 20 meters across, there

is a chance you’ll miss. If you want to hit that rock in our example you’ll

need to keep the eyes open! In the open mountain areas, things are of course a

lot easier when you can see far ahead of you. The only way to learn this

properly is to try it in the backcountry. Well that is until the fog comes. Fog

can make orienteering in the mountains and in the forest extremely difficult,

and therefore, it can also be dangerous to the unexperienced.

we say that as a rule of thumb, the uncertainty is one tenth of the distance

traveled. So if it is like in the figure, you go 200 meters on course, it

is possible that you end up a little off course, 20 meters or so. If

you’re looking for something smaller than 20 meters across, there

is a chance you’ll miss. If you want to hit that rock in our example you’ll

need to keep the eyes open! In the open mountain areas, things are of course a

lot easier when you can see far ahead of you. The only way to learn this

properly is to try it in the backcountry. Well that is until the fog comes. Fog

can make orienteering in the mountains and in the forest extremely difficult,

and therefore, it can also be dangerous to the unexperienced.

How

to navigate in foggy conditions

to navigate in foggy conditions

Fog makes things difficult,

and in some situations dangerous. When you hike, you will probably some day

experience these difficulties, and you’d better be prepared. The fog can come

creeping very fast. I have myself experienced from clear view to dense fog in

10 seconds. How fast this goes, depends on where you are. In normal summer

conditions without snow, it is often not much of a problem. Unless you are

supposed to find a hut or something. The ground provides normally so much

contrast, you could do the aiming I have written about in lesson 2. Just be very careful and accurate. Perhaps you also

might use some of the advice given later.

and in some situations dangerous. When you hike, you will probably some day

experience these difficulties, and you’d better be prepared. The fog can come

creeping very fast. I have myself experienced from clear view to dense fog in

10 seconds. How fast this goes, depends on where you are. In normal summer

conditions without snow, it is often not much of a problem. Unless you are

supposed to find a hut or something. The ground provides normally so much

contrast, you could do the aiming I have written about in lesson 2. Just be very careful and accurate. Perhaps you also

might use some of the advice given later.

Winter conditions can make

things a lot worse, when there is snow on the ground. The fog is white (or

grey), the snow is also white. You may get a condition we call a “white-out”. It’s too late to read the terrain, and then the map

isn’t of much use. You can’t see anything anyway. You have no choice but to put

blind faith in your compass. I hope you knew where you were, because you need

to take out a good compass course, like described in the other lessons. If you

are skiing, you should tie your compass to your arm or something, so you can

look at it for every step you take. A rubberband is good. Check for more or

less every step you take that the compass needle is aligned with the orienting

lines. But if it is cold, make sure it doesn’t affect circulation of blood

in your arm, because that will make you freeze. If you are going on an

expedition where you expect conditions like this, you should perhaps consider a

arrangement to attach to your chest.

things a lot worse, when there is snow on the ground. The fog is white (or

grey), the snow is also white. You may get a condition we call a “white-out”. It’s too late to read the terrain, and then the map

isn’t of much use. You can’t see anything anyway. You have no choice but to put

blind faith in your compass. I hope you knew where you were, because you need

to take out a good compass course, like described in the other lessons. If you

are skiing, you should tie your compass to your arm or something, so you can

look at it for every step you take. A rubberband is good. Check for more or

less every step you take that the compass needle is aligned with the orienting

lines. But if it is cold, make sure it doesn’t affect circulation of blood

in your arm, because that will make you freeze. If you are going on an

expedition where you expect conditions like this, you should perhaps consider a

arrangement to attach to your chest.

Let’s consider a method to

enhance the accuracy in conditions when you can’t aim at anything. If you are

three persons in a row, like on the figure, and the last one carries a compass

(of course, it is better that all three carry a compass, but the last one has

command), he or she will see if you get off course because one of those in

front of him or her will not be covered by the person in front. On the figure,

the situation to the left is ok. The person on top is heading forward and but

he sees only the person in front of him or her. In the situation to the right,

it’s time to stop. The last person can see the backs of both of them in front,

and they are about to leave their course.

enhance the accuracy in conditions when you can’t aim at anything. If you are

three persons in a row, like on the figure, and the last one carries a compass

(of course, it is better that all three carry a compass, but the last one has

command), he or she will see if you get off course because one of those in

front of him or her will not be covered by the person in front. On the figure,

the situation to the left is ok. The person on top is heading forward and but

he sees only the person in front of him or her. In the situation to the right,

it’s time to stop. The last person can see the backs of both of them in front,

and they are about to leave their course.

The further apart you go,

the more accurate this method is, but it is also very important to have good

contact. Sometimes the conditions get so bad there is no way to maintain

contact, and then, the method may fail. There is also another method for two

people, where the lead person goes out on a compass azimuth, as far as the

visibility will allow. The person behind stands still and watches the lead

person, telling them if they are in the correct line or not. Once they have

moved correctly into line they then stand still and the back person joins them.

They then have their turn to move out ahead on the azimuth, and the whole cycle

repeats. The problem with this method is when the visibility is very bad, the

lead person can’t go more that a few meters, and it would be dangerous to loose

each other.

the more accurate this method is, but it is also very important to have good

contact. Sometimes the conditions get so bad there is no way to maintain

contact, and then, the method may fail. There is also another method for two

people, where the lead person goes out on a compass azimuth, as far as the

visibility will allow. The person behind stands still and watches the lead

person, telling them if they are in the correct line or not. Once they have

moved correctly into line they then stand still and the back person joins them.

They then have their turn to move out ahead on the azimuth, and the whole cycle

repeats. The problem with this method is when the visibility is very bad, the

lead person can’t go more that a few meters, and it would be dangerous to loose

each other.

Finally, I’d like to comment

on something that is seen in many standard texts on mountaineering navigation:

You are commonly taught to use methods that use terrain features that are

easily recognizable but far away. In my opinion, such methods are of little

use, unless you require surveyor’s accuracy in knowing where you are (hikers

rarely do). As long as the weather is good, navigation is fairly easy and

you’ll naturally use these features as part of a more general approach.

However, when the visibility is poor, you can’t see these far-away-features and

this makes the methods involving them rather useless. Therefore, focus your

training in navigation on using features in your vicinity.

on something that is seen in many standard texts on mountaineering navigation:

You are commonly taught to use methods that use terrain features that are

easily recognizable but far away. In my opinion, such methods are of little

use, unless you require surveyor’s accuracy in knowing where you are (hikers

rarely do). As long as the weather is good, navigation is fairly easy and

you’ll naturally use these features as part of a more general approach.

However, when the visibility is poor, you can’t see these far-away-features and

this makes the methods involving them rather useless. Therefore, focus your

training in navigation on using features in your vicinity.

Kjetil Kjernsmo’s (1997-2000) illustrated guide on how to use a compass. http://www.learn-orienteering.org/old/fog1.html kjetikj@astro.uio.no